🧵 View Thread

🧵 Thread (23 tweets)

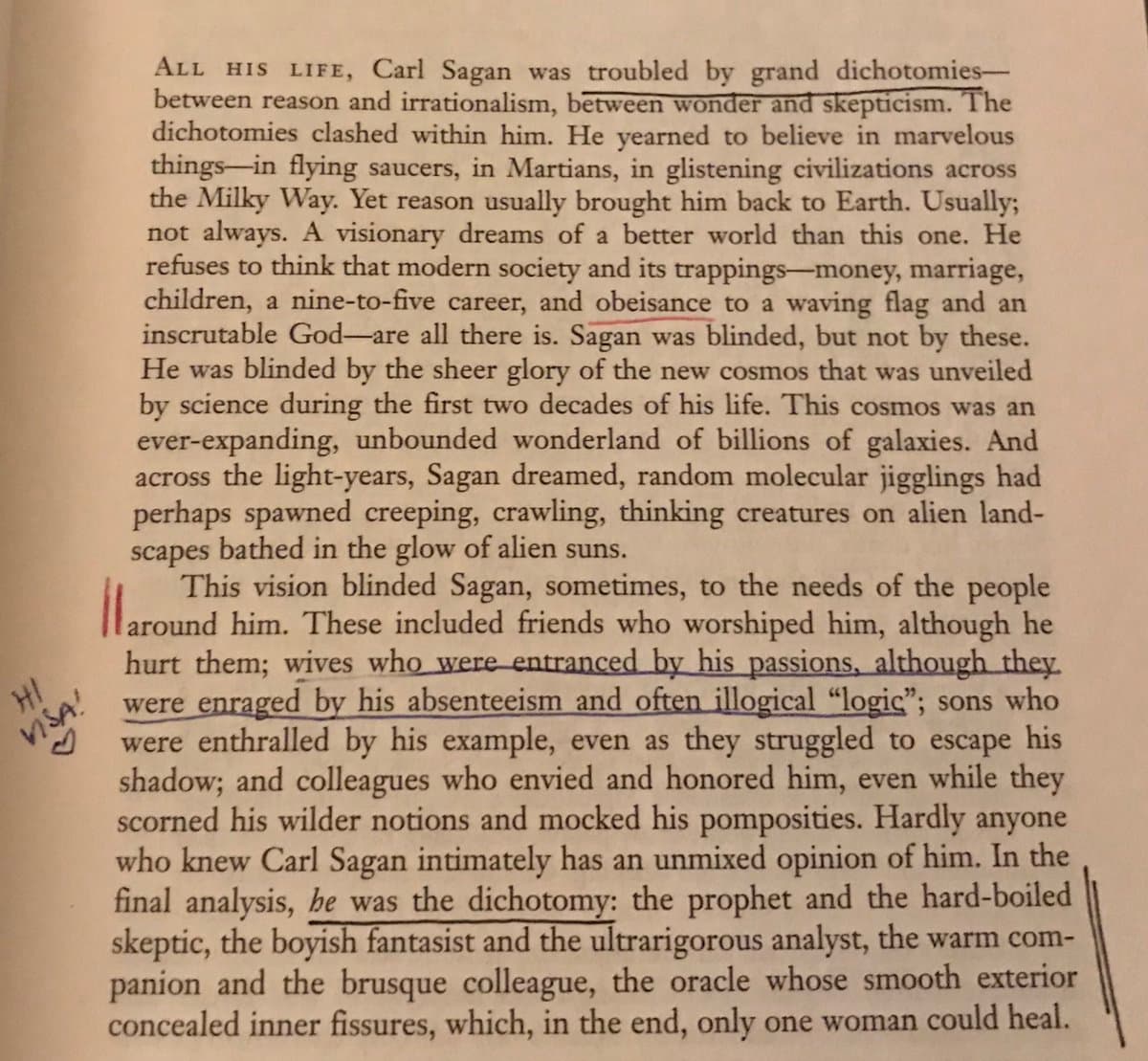

When I was about 20, I read Keay Davidson’s biography of Carl Sagan and I remember being extremely moved. I’ve forgotten practically all of the details, and it’s been such a long while that I’m pretty excited to read it again https://t.co/JUsCetxILT

In 1969, when Keay was 16, he read Sagan and Shklovskii’s ‘Intelligent Life in the Universe”. He was entranced by an image of a million stars near the center of the Milky Way, and the prospect that one of them might be the Sun to an advanced alien civilization https://t.co/eF69og3q2v

“People can believe in rational things for irrational reasons. [...] the history of scince makes more sense if one takes into account non-rational factors (social prejudices, political tendencies, religious influences and so on.)”

1966: USA and USSR had narowly averted the Cuban Missile Crisis. The idea that Soviet and American scientists might coauthor a book was fantastic to a generation of schoolchildren raised on cold war propaganda and “duck and cover” exercises at school

Sagan was different things to different people - to young people, his eloquence was an irresistable summons to scientific careers - to his colleagues, he was a sometimes stimulating, sometimes upsetting gadfly who proposed both brilliant and irresponsible ideas

To NASA, Sagan was its most valued – albeit unofficial and erratic – propagandist To diehard cold warriors, he was a fuzzy-headed, left-leaning academic who meddled in the machinery of nuclear weapons policy To some conservatives, he was a suspicious symbol of secularism

“But to the general public – which tends to resent science for undermining religious faith and New Age folklore – he offered an alluring compensation for all that science has destroyed.” (My teenage marginalia: “you have to do that to win people over”)

As a scientist, Sagan speculated freely, sometimes wildly, and outraged his more cautious colleagues. A few regarded him as a charlatan. Some of his closer mentors (Gerard Kuiper, and Harold Urey) nursed serious doubts about his sense of scientific responsibility.

“Science often advances via lucky guesses, offbeat hunches, reckless speculation. This is especially true of “frontier” sciences such as space science, where little is known and the race often goes to the swift and the imaginative rather than to the plodding and cautious.”

“The price of fame is a big head, and Sagan’s head grew mighty big; eyewitness testimony to this effect abounds. As much as I admired him, I was always bothered by his seeming omniscience. Nothing seems to rattle him [...] he had an answer (sometimes glib) for everything.”

“Now that I have explored his life for two years, his imperturbability strikes me less as arrogance than as a half-conscious pose. [...] Hyper-dignified, above-it-all, judgelike... That public perception accounts (justifiably or not) for much of the prestige of science.”

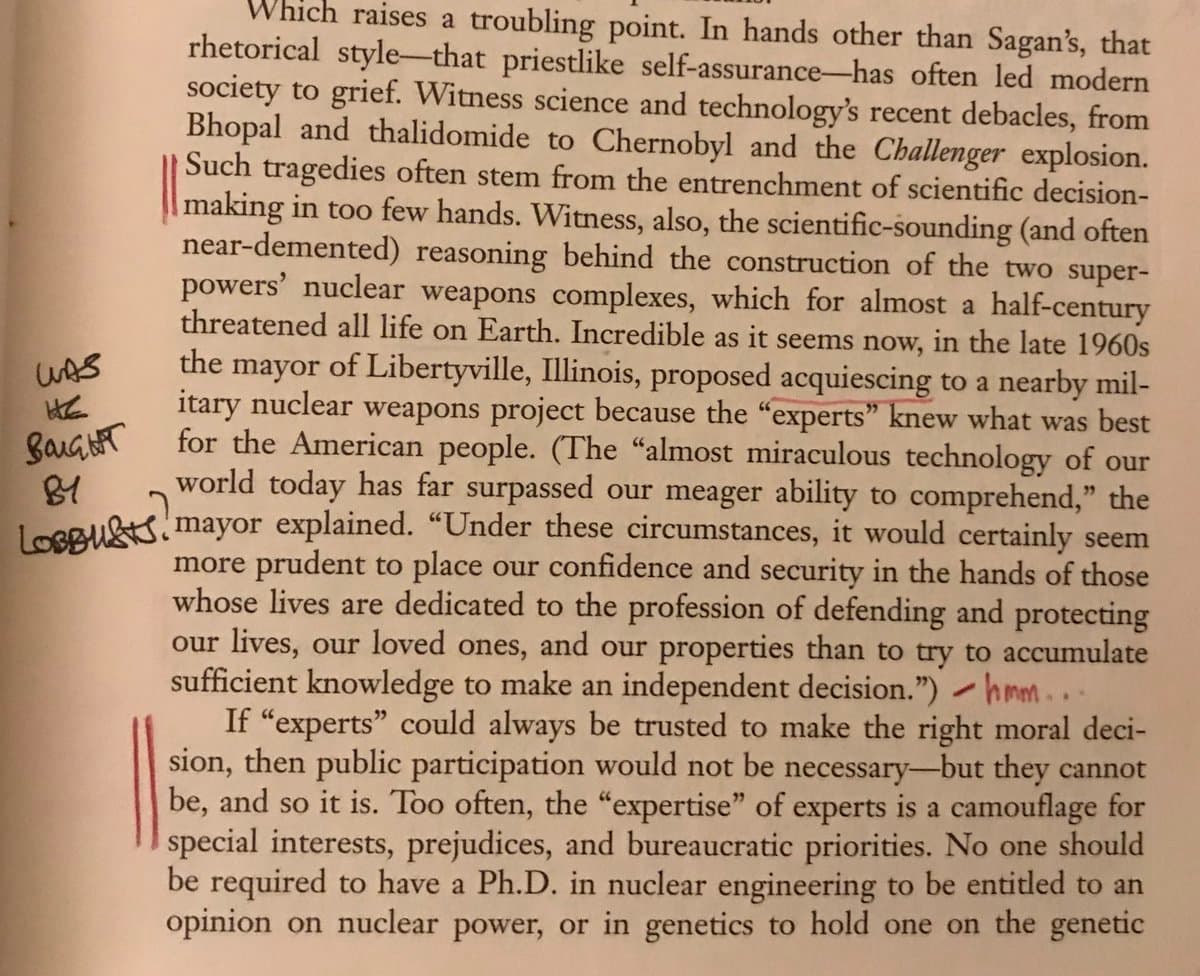

Troubling: “In hands other than Sagan’s, that priestlike self-assurance has often led modern society to grief – from Bhopal and thalidomide to Chernobyl and the Challenger explosion – tragedies too often stem from the entrenchment of scientific decision-making in too few hands.”

In the late 1960s, the mayor of Libertyville, Illinois proposed submitting to a nearby military nuclear weapons project because the “experts” knew what was best. “Almost miraculous technology... surpassed our meager ability to comprehend...” https://t.co/ZR7IVVPXHy

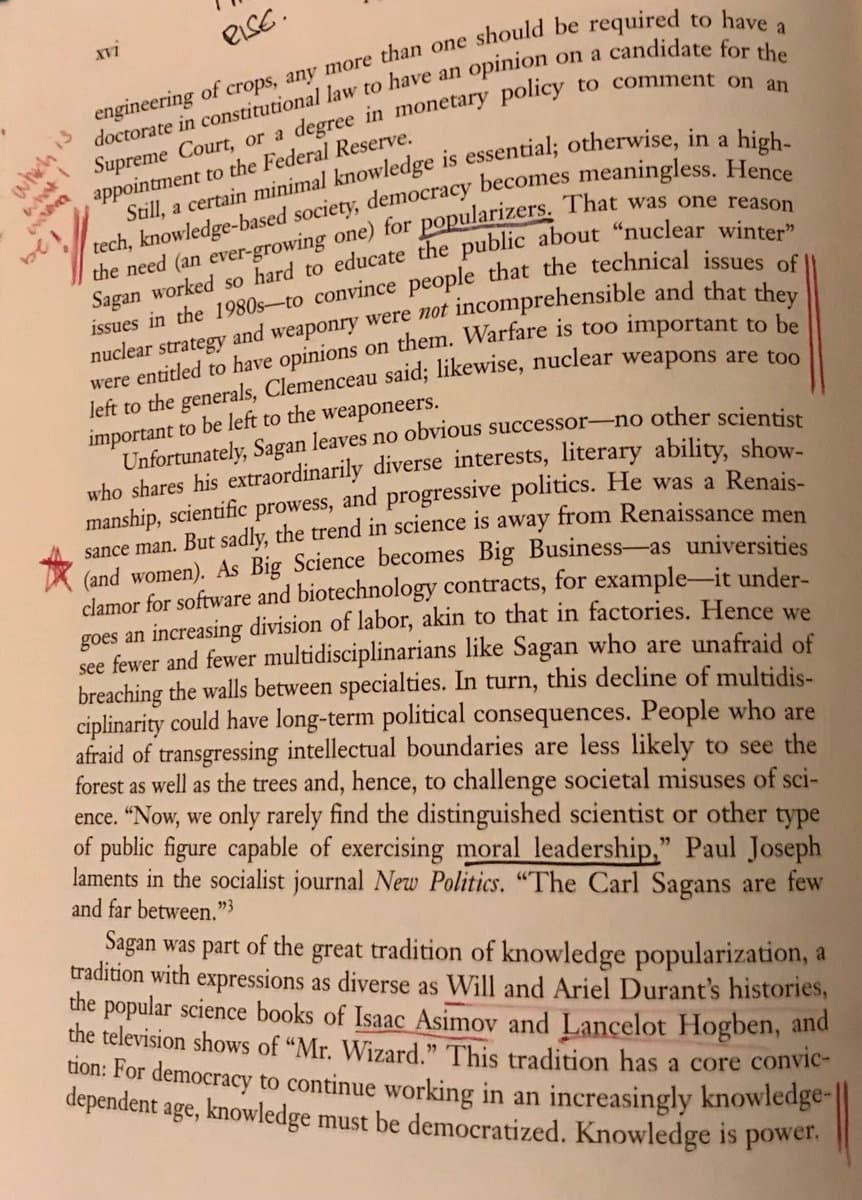

“Still, a minimal knowledge is essential, otherwise [...] democracy becomes meaningless. Warfare is too important to be left to the generals.” Re-reading this, I find myself thinking “but what about misinformation??” – I guess it simply wasn’t as big of an issue back then https://t.co/3QXfDbXfoJ

... my wife has been reading this 😅 https://t.co/xzJIv1sfsQ

There’s a lot of interesting details about Sagan’s parents, and of the times they lived through. The war-mad 1910s, the money-mad 1920s, the bleak Great Depression of the ‘30s. Keay spends some time talking about Freud, Einstein, the Jewish people.

“Freud’s outlook grew dark as Europe tore itself to bits in one war, then rearmed for a worse one; and darker as the cancer attacked his body.” This is what I love about biographies – big picture perspectives on the broad, hard-to-see-in-real-time forces that shape people’s lives

Guidebook for immigrants: ‘Hold fast, this is most necessary in America. Forget your past, your customs, and your ideals. Select a goal and pursue it with all your might. You will experience a bad time but sooner or later you will achieve your goal. Do not take a moment’s rest.”

Wtf: In the 1930s, fascists blamed The Great Depression on Jews. FDR was attacked by bigots for his “Jew Deal”. ^ reading this as a teenager didn’t really mean very much to me (I did scribble “dafuq” in the margins), but in 2018 it feels... prescient? Prophetic?

1939 – USA groggy from Depression. Hitler in Europe, militarists in Japan. Yet Americans were optimistic– fabulous new tech would eliminate poverty, hunger, illiteracy! Synthetic foods for starving, miracle drugs for the sick! TV would bring high culture into every home for free!

"Tech propaganda promised to improve society w/o class revolts or ideological bickering. How? Tech = embodiment of Enlightenment rationalism. Rationalism = road to Truth, optimal solutions for all problems, regardless of class, ethnicity, nationality." (Gender wasn't a priority)

"Therefore, the propagandists argued, tech, being reason's physical embodiment, was inherently non-ideological. Its control could be entrusted to politically neutral "experts", whose goals was the greatest good for the greatest number. Who could question such a noble agenda?"